We took the bus back to El Calafate yesterday and said our good-byes to Monte Fitz Roy (Fitzie), Cerro Torre and the whole of El Chalten. Being in a bigger and busier town has its pluses, but walking along the main drag with all the amenities brought me closer to home and reminded me that we’re halfway through our two-week vacation. For the first time in almost a week though, we finally saw the sun set. Here in Patagonia, the sun sets at around 11pm and we’ve missed the last few because we would be indoors, inebriated from too much red wine and comatose from the day’s hike. (Cue in song, With a Little Help From My Friends…)

I fall in and out of sleep while on the bus to Perito Moreno Glacier, only to wake up with the same view around me: big mountain in front, water on the left, forest on the right; but no ice. It’s been more than an hour and I just can’t wait to get out of the bus and stand up. At the park’s entrance, a guide goes around with a small ticket machine charging us $60 Argentinian (about US$20) to enter. A few on the bus only had to say, Nacional, and they get a citizen’s discount at $20 Argentinian. This is the first time my group is charged for any sort of activity in Patagonia and all eyes are on me to make sure the fee is worth it.

Back in New York, I’ve signed everybody up to do a mini-trek on Perito Moreno instead of just a bus ride to view the giant glacier from the balcony. It cost each of us US$100, which we all consider steep since we’re not the kind of travelers who pay for organized tour groups. But there is no such thing as shopping for a tour guide to do the mini-trek. Hielo Adventura has the monopoly to ferry tourists across the lake, suit them up with crampons and lead them on the glacier for an hour and a half before sending them back to their hotels. I later appreciate this because I couldn’t imagine hoards of people on the glacier trekking everywhere if one outfit didn’t control the number of visits to the top.

So what is a glacier? It’s technically a big mass of ice with two zones: accumulation and percolation. It’s constantly snowing in the accumulation zone while the ice is melting in the percolation zone. The ice moves down the slope from where they are situated and ends in lakes or cliffs and forms terminal moraines, or stones and dirt pushed by the glacier.

Named after the Argentinian explorer Francisco Pascacio Moreno, the glacier is popular because it’s one of the few that can be accessed as simply and easily as this. While most glaciers are in very high altitudes and extreme temperatures, Perito Moreno is only 50 miles from El Calafate and only 279 feet above sea level. Since 1917, the glacier has been stable: its surface, width and length have remained the same because the snow increase in the accumulation zone is enough to compensate for whatever’s melting in the percolation zone. Moreno acted as the expert–that’s why he was called perito–when the Patagonian border was being disputed between Argentina and Chile and donated the land for the first Argentinian National Park, but he never saw the glacier that was named after him.

We spend about twenty minutes ooh- and aah-ing at the glacier. It really is amazing how massive and far out it goes. The wind is steady and it’s warm enough to stay at the balcony with cameras in hand, waiting for a small piece to crack and fall into the river. (It’s probably one of the few places where you can hear people beg for the glacier to start cracking.) Whenever there is a crack–and it happens every few minutes–there is a thunderous noise, followed by a loud snap, like a gunshot, when the ice falls into the river. No matter how small, the fallen ice creates a ripple and another loud whoosh occurs. Everyone is on high alert when this happens because they want to capture the action on film, but most of the time, the crack happens somewhere we can’t see. There is always a cheer from people who catch the exact moment and it’s funny how automatic the reaction from the crowd gets after a few minutes.

Two hours later, we board the bus to the pier and then the ferry across Rico Arm. From the boat, we can see the glacier’s front walls and some iceberg channels. Everything is of that blue-ice color. (Oh, why? Snow and ice is white, but when sunlight goes through a glacier’s solid ice crystals, it gets broken down into different colors. Blue light has enough extra energy to get away from the crystals without getting absorbed by the thick ice, so we see that blue that “escapes”.)

On the other side, we hike through a forest and see the contrast of the earth against the blue ice. It’s like walking into some kind of video game: dry land here, water in the middle, ice over there. All you have to do is hop over and you’re in a completely different landscape. One of the guides, after hearing that I’m from New York City, tells me that one of the most important movies shot in the city is also his favorite movie of all-time: Madagascar. I laugh, join in the joke and tell him that the penguins are probably still up to no good. The Dr. remains stoic because he never saw the movie. We put our crampons on.

We see several groups of twenty ahead of us. The guides smartly separate all of us in a timely manner so that we all enjoy the glacier at our own group time. It’s never crowded while we trek and we never come across the other folks. We trek in one line and follow our guide, hunching forward when walking and leaning back when descending. I love the sound of crushing ice and I over-react and march with my knees up to get more of it. I take photos after photos of cracks and crevices and of small pools and trickles. I can’t get enough of the view. Ahead of me, the ripples of ice look like a meringue. It’s like some giant hand came down and whipped the ice to make soft peaks, you know? I know that sounds really gay, but it’s just that everything looked saaawft.

We stop where we drank from the small pond that has formed on the ice. The water is naturally cold and refreshing, but we still manage to convince ourselves that it is the best-tasting water we’ve ever had. For only US$100!

I jump when the guide isn’t looking and we do ridiculous poses when we get a chance to stop. They take us to small caves and let us peek down dangerous crevices. We walk across thin ice, jump over safe indentations and hike up and down small hills to get a feel of the massiveness of Perito Moreno. We end at a table where our guide chips off glacial ice to drink with the Famous Grouse whisky they’ve set up beforehand. Everyone toasts and munches on the dulce de leche candies they distribute. It’s the perfect end to our day.

Later, the group tells me that the money they paid was all worth it.

Related post/s:

Perito Moreno Glacier photos on Flickr

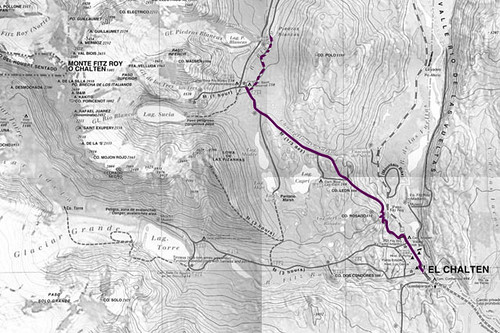

Day 3: Hiking to Cerro Torre

Hielo Adventura